Liar, liar pants on fire – do lie detector tests really work?

POLYGRAPH tests are becoming big business but do they really work? Brad Crouch put on his best poker face and tried to outsmart the experts at Australian Polygraph Services

By Brad Crouch, The Advertiser.

July 05, 2013

The stomach butterflies are doing battle as my heart pumps and my buttocks clench. My eyes are shut and my toes are frantically searching for a pin hidden in my shoe.

The stomach butterflies are doing battle as my heart pumps and my buttocks clench. My eyes are shut and my toes are frantically searching for a pin hidden in my shoe.

None of it matters. When I utter a single-word lie the cold clinical lines on a computer monitor catch me like a kangaroo in a spotlight.

In the world of polygraph examination neither natural nervousness or tricks like bum crunches or painful toe pokes seem capable of disguising a fib from a trained examiner.

Critics dismiss polygraphs as unscientific, and crusaders like George Maschke who runs website www.antipolygraph.org liken them variously to witchcraft, voodoo, astrology and tarot, and cites the National Academy of Science and US National Research Council as issuing reports critical of polygraph accuracy.

However, lie detectors are used by agencies ranging from America’s Pentagon and Homeland Security to South Australia Police.

In mankind’s search for a sure-fire path to the truth, which has ranged from water torture to truth serum, polygraphs are the instrument of choice.

Today it is a growth area, and not just in crime. The big business is in areas such as suspicious partners testing for fidelity, concerned corporations checking for insider spies and even worried parents checking children for drug use.

While polygraph results are not used in courts in Australia, demand from individuals, corporations and police forces has seen steady growth for truth testers over the past decade.

Australian Polygraph Services (APS) run by two former police officers is surfing this wave.

Michelle Chantelois underwent a polygraph test after she claimed to have had an affair with then South Australian Premier Mike Rann. The polygraph indicated she was being truthful – but Mr Rann has strenuously denied her claims. Picture: Matt Turner

Victorian-based Steven Van Aperen founded the firm after visiting the FBI academy in Quantico, Virginia, as a Victorian policeman to train in psychological profiling. He came across polygraph work and his career took a new turn.

He now also gives corporate seminars on how to spot a liar using physical giveaways, based on methodology and training rather than guesswork, and even has a website under his nickname, the Human Lie Detector.

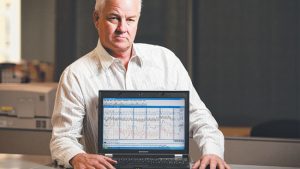

He and Adelaide-based Gavin Willson conduct polygraph tests all over the nation, often as simple fly-in, fly-out examinations. The machinery is portable and can be taken on aircraft as carry-on baggage, with a laptop replacing bulky roles of paper to record changes in physiology under questioning.

Both men trained in the US where polygraph services are far more widely accepted including in some courts and have had ongoing training there.

While the science behind polygraph testing is complex, it can be broken down into fairly simple terms. A subject is hooked up with equipment which measures autonomic reactions, or involuntary changes in cardiovascular function, perspiration and respiration. In layman’s terms, uncontrolled changes to blood, sweat and breath.

In a calm atmosphere, and after preliminary preparation to adjust the equipment to the individual, the subject is asked a series of bland questions which everyone knows the correct answer to such as “Is your name so-and-so?” and “Is today such-and-such.”

The subject has eyes closed to reduce distractions with feet placed flat on the floor. There is no one else in the room apart from the examiner and there is a 25 second gap between each question.

Then comes a pivotal question, framed so it is clear and unambiguous. Physiological changes triggered by our “flight or fight” response automatically come into force affecting blood pressure, sweat and breathing. The machine records them and an experienced examiner can draw conclusions.

In a typical examination the subject will be asked the key question several times, in between random bland questions, over an extended period for comparison.

Polygraph expert Gavin Willson interviews Brad Crouch. Picture: Dylan Coker

Polygraph expert Gavin Willson interviews Brad Crouch. Picture: Dylan Coker

The instruments don’t actually state whether a person lied. They do record physical responses which appear to record when people feel anxious or afraid – which is how most people feel when they fib.

“People don’t feel comfortable lying,” Willson says. “Everybody lies, and some people even pride themselves on being a good liar, but US research shows there are physiological changes in response to given stimuli.

“We have a fight or flight response which triggers changes to things like the pupils, blood pressure, heart rates; they are all part of changes that result from fear and anger. And they can be measured.”

The key question needs to be concise, and while the questions are in random order there are no surprises – anyone volunteering to undergo a test knows exactly why they are in the room, be it over fidelity or fraud.

If the issue is highly emotive, for example allegations of sexual assaults on a child, Willson might have the person sign a declaration denying the allegations, then simply ask if the declaration is correct.

Virtually everyone is nervous going into such a test, even people with nothing to hide, but these nerves are factored in with a separate period of preliminary questions unrelated to the main issue in order to calibrate the instruments.

The stomach butterflies, the pumping heart and concentrated breathing due to nerves are checked against the preliminary results, and don’t worry if sweat is running down your forehead – tiny monitors check microscopic perspiration from fingertip glands, not your face.

“The most common question I get is, ‘Will nerves affect the test?’ and the answer is ‘No’,” Willson says. “If it did everybody would fail. Everybody is naturally nervous when they do a test.”

Tricks to fool instruments – the old tack in the shoe trick, or clenching the sphincter to try to change blood pressure and breathing patterns – should be spotted by an experienced examiner.

Websites devoted to how to fool a lie detector test give advice such as getting a good night’s sleep, building a friendly rapport with the examiner and staying calm to try to control blood, sweat and breathing patterns.

They also recommend things like using a tack in the toe or bum crunches during the bland questions to raise blood pressure and breathing rates, then staying calm during the pivotal question, to distort overall results. Willson chuckles at these.

“Examiners read those websites too,” he says. “If I think someone has a tack in their shoe I make them jump up and down or take the shoe off. The reality is, we tend to know when people are messing with us.”

The standard APS answer to whether people can beat the test is: “People don’t beat a polygraph test, they beat the examiner conducting the test.”

Willson emphasises a proper test is not just a reading from the instruments; it involves the examiner fully understanding the situation and formulating concise questions to elicit clear answers.

It also requires an examiner skilled in both reading the instrument’s result and also “reading” the subject to see if they are co-operating.

One of four results will be returned: Truthful, Deceptive, Inconclusive or Purposeful Non Cooperation, the latter being when someone is obviously (to the examiner) trying to fool the instrument.

Willson says a trained examiner can spot someone trying to distort the instrument readings relatively easily, and APS has a policy of giving such subjects three verbal warnings.

His US training also includes interrogation techniques and body language to spot a lie, an area he says is greatly misunderstood by many people.

“Some people think if a person is crossing their arms they have something to hide, or if they scratch their nose they are lying but sometimes they just have an itchy nose,” he says. “There are many pointers in body language but you have to have a base to work from.”

Supporters of polygraph examination point to hundreds of scientific analyses done in the US which show a success rate of around 98 per cent.

Detractors say they are unreliable, and note sceptical reports such as one by the US National Academy of Science which called them “unscientific”.

However, polygraphs are used widely in the US where they are accepted in some courts at various stages of proceedings and are used by Government security agencies as a screening tool.

Willson has seen business grow steadily since he gained his qualifications a decade ago and now does more than 100 tests a year, as people become more aware the service is available.

High profile cases, such as Adelaide woman Michelle Chantelois’ test with APS, which appeared to confirm her allegations of an affair with then-premier Mike Rann which he denied, are good for business while these days a simple Google search makes it easy to find a truth-sayer.

Other high profile cases where APS has conducted polygraph tests include on people involved in the Azaria Chamberlain case, the Schapelle Corby case and the Howard Government’s “children overboard” scandal.

In Australia the results cannot be used in court but APS say they have been called in to consult on more than 70 homicide cases around the nation.

In South Australia, SAPOL says it does not use polygraphs in criminal investigations as there are inherent risks and the data is inadmissible in court.

However, SAPOL confirmed its Police Recruiting unit has used polygraph testing for pre-employment checks since 2008 – a practice likely to spark uproar if adopted by the corporate world.

Attorney-General John Rau says the State Government has no intention to permit the use of polygraph machines in the criminal justice system.

“Questions about the accuracy and the ability to manipulate the output of these machines remain unresolved,” Rau says.

“Even if their accuracy was 100 per cent, their use could only ever be considered during the course of an investigation not in a court.”

While TV shows tend to show polygraphs as instruments to find a criminal, Willson says often their use is in helping someone clear their name or narrow a pool of suspects.

In any group of suspects it is more likely to be the innocent clamouring for a test to clear their name, helping investigators focus their inquiries. It can also prompt confessions.

With no compulsion on anyone to take a test, simply volunteering for a test or refusing one can be a pointer for someone probing a corporate or domestic drama.

APS says corporations use their services in cases of theft, fraud, and other crimes, sometimes to avoid the unwanted publicity of a police investigation.

APS says polygraphs have been used in cases involving allegations of kickbacks, professional misconduct, sexual harassment and industrial espionage. The casino and racing industries have sought polygraph services, as have sporting bodies worried about drug use.

The delicate nature of lie detection means people seeking such services want discretion and also are discreet themselves. Willson found himself on one interstate assignment checking a suspected theft of an object where it turned out the aggrieved owner had himself obtained it illegally.

However, the big growth area is in domestic situations. “A very common area now is around fidelity issues, where a partner wants a spouse, fiance or partner tested,” Willson says.

“There are also allegations of sexual assault, often where people want to clear their name.”

Blended families and marriage break-ups are brisk business, for example where a child makes an allegation about a mother’s new partner.

“In a custody case you might find a woman suddenly makes an allegation against the man regarding a child, and the man is looking at all ways to clear his name,” Willson says.

Parents also are seeking to have children suspected of taking drugs tested. Willson said this is not a regular occurrence but it is happening.

Domestic cases can be emotionally-charged but by the time they get to the stage of taking a polygraph exam those involved have usually vented much of their anger. Willson also noted APS has had referrals from marriage counsellors.

“Counselling won’t answer the one question the unhappy partner wants asked – whether their partner has had an affair,” Willson says. “But if people need a polygraph test they might not have a great relationship to start with.”

Answers won’t always be what everyone wants, and may throw up the unexpected such as the case reported in Britain when a man wrongly suspected his wife of having an affair.

When asked if she had ever had sex with a man other than her husband she answered “no” and the instrument indicated she was lying. It emerged she was raped as a child and had kept it secret.

The search for truth now has extended beyond polygraphs. The Smithsonian Institute reports we have come a long way since India 2000 years ago when rice was put in a suspect’s mouth during questioning. If the suspect could spit it out afterwards he was telling the truth, if not his parched throat indicated a liar.

Work continues on using P300 brainwaves, and MRI images, to reveal lies, while the Smithsonian says the US Secret Service uses “Wizards” to scan crowds for troublemakers – agents with a phenomenal natural ability to spot deception and odd behaviour.

Wizards aside, the polygraph remains the lie detector of choice.

So now it is time to see how the instrument works.

Willson prepares me for a “peak of tension” test, part of the overall examination that usually takes up to three hours.

It is the same test given to all subjects as a pre-cursor to asking the main questions, in order to adjust the instrument to the individual.

He puts small sensors on the second and fourth fingertip of my right hand, to measure microscopic changes in sweat from glands in the fingertips.

Two pneumograph tubes are placed across my chest and abdomen to measure respiration, and a blood pressure cuff is put on my upper left arm.

The test is so simple it is almost ridiculous. Before we start Willson asks me to pick a number between one and six, then gets me tell it to him.

It is number five.

He then tells me to lie to him when asked, “Is it number five?”

So, to get this straight, he knows my number, and I know he knows my number; he knows I am going to lie about my number, and I know he knows I am going to lie.

He asks me to shut my eyes to block out all distractions, keep my feet flat on the floor then asks me a series of questions in no particular order with a 25 second gap in between each.

“Is it four?”

“No.”

“Is it two?”

“No.”

From the start I am as nervous as hell, my guts are churning, I can feel my blood coursing and can’t stop visualising “5” in my mind. I am innocent, this is just a test for a story, the examiner even knows I will lie about the number, and I know he knows. I am surreptitiously bum crunching and toe fiddling during these questions but doubt this makes any difference to my already racing heart and formal breathing.

“Is it five?”

I remain as calm and serene as possible.

“No.”

The Zen strategy fails. When I am unhooked later Willson shows me the computer read-out from the various sensors. There is a clear “blip” on the relevant question, which he reads as deception.

Critics might baulk at the idea an instrument can measure emotion to a point of separating fact from fiction, but in this case being hooked up and questioned triggered emotional responses that manifested as physical changes.

This was just a little test for a story, a parlour game of truth or dare to see the instrument in action.

In a more serious setting, as the nerves grow along with compulsion to confess any guilt, it might be time to consult John 8:32. “And you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

From the Australian Polygraph Services file

- A businessman accused of sexually molesting his daughter sought a test after a police investigation found no evidence but on-going rumours threatened his career and marriage. He passed the test.

- A national retail chain investigating a $25,000 theft from an office safe arranged to have staff tested. Seven people agreed to the tests and passed, before a staff member due for a test confessed.

- A multinational company based in Asia used tests on staff to check if anyone was receiving kickbacks for awarding multi-million dollar supply contracts. A staff member who returned a deceptive result admitted receiving cash and goods from a supplier in return for awarding a contract.

- A company sought polygraph tests for employees when a cheque was fraudulently altered. An employee who failed the test admitted he made the alterations as a result of his gambling addiction.

- A man agreed to his wife’s demand he undergo a test when suspected of an affair. He failed and offered the examiner a $5000 bribe to change the results which was rejected. He then admitted to an affair with his sister-in-law.

- A mother who found large amounts of cash in her teenage son’s bedroom suspected him of selling drugs. She arranged a test which asked if he was selling drugs and he passed. He later admitted he was committing burglaries with a friend and selling stolen goods.

- A married woman subject to office gossip she was having an affair requested a polygraph test to prove her innocence. She passed and circulated the report in her office to quell malicious rumours which jeopardised a promotion.